Leadership implications in complex projects: The Boeing DreamlinerProject Management, Project Control, Earned Value Management (EVM)

Leadership implications in complex projects: The Boeing Dreamliner and Jim

McNerney1

Gina Vega

Organizational Ergonomics

Note to Faculty: There is a teaching note available to faculty only for this case. To obtain the document,

please request it directly from the PMITeach.org administrator at pmcurriculum@pmi.org on your

school letterhead.

In defense of criticism of Boeing’s 787 production delays, CEO Jim McNerney explained:

We are trying to come up with the strongest set of partnerships we can with the people that

supply our major systems and structures. In defense, we are trying to respond to the pressures

of governments buying fewer things at lower prices, with less favorable contract terms. And that

pressure cannot just stop at Boeing. We have to find willing partners [to share the burden]. And

on the commercial side, low-cost carriers and a very flattish global economy leads you to the

same conclusion. So the ‘no-fly list’ is people who don’t want to play ball, who only want to hide

behind the contractual language of their current programs. We’re going to give those who do

want to work with us more business—or we’ll move some things in-house. This is a not a rape,

pillage and plunder exercise. This is the reality we all face. The majority of [suppliers] are

beginning to have productive discussions with us. We have some holdouts, people who take the

position that the pressure should only be absorbed by Boeing, notwithstanding the fact that 65

percent of most of our airplanes are built by suppliers…we both have to demand lots of

productivity [improvements] to offset price pressure. Those that work with us in that way will

find more volume. We are the biggest player. My message is, ‘Don’t bet against us.’i

The Boeing Dreamliner

Boeing Corporation was one of the world’s largest manufacturers of commercial aircraft, ranking 27th

on the Fortune 500 list in 2016. When it announced the delivery of its first 787 Dreamliner transporter

to its first customer, All Nippon Airways, in September, 2011, it was almost 40 months later than

originally planned, after a long series of unexpected delays. The actual development cost of the project

had been estimated at about US$40 billion but came in over twice the original estimate. One year later,

a malfunction was discovered in one of the aircraft’s lithium batteries, which caught fire after takeoff.

These problems led to months of grounding, imposed by the FAA (Federal Aviation Administration), of

the entire Dreamliner fleet already in service.

The Dreamliner was designed to be a revolutionary project in terms of physical characteristics,

technology, management style, financing, design and engineering management, quality assurance, and

assembly processes. Many of these initiatives were intentionally taken on to benefit from new

developments in aviation technology and to speed up design and development; however, they posed

unexpected challenges for both the company and the project team.

1 This case is based on Shenhar, A.J., V. Holzmann, B. Melamed & Y. Zhao. (2016). The challenge of innovation in

highly complex projects: What can we learn from Boeing’s Dreamliner experience? Project Management Journal,

Vol. 47, No. 2; 62-78.

A New Organizational Paradigm

Boeing adopted a new organizational paradigm for the development of Dreamliner and decided to

outsource an unprecedented portion of the design, engineering, manufacturing, and production to a

global network of 700 local and foreign suppliers. With more than 70% foreign development content,

this decision turned Boeing’s traditional supply chain into a development chain. Tier-1 suppliers became

responsible for the detailed design and manufacturing of 11 major subassemblies, while Boeing only did

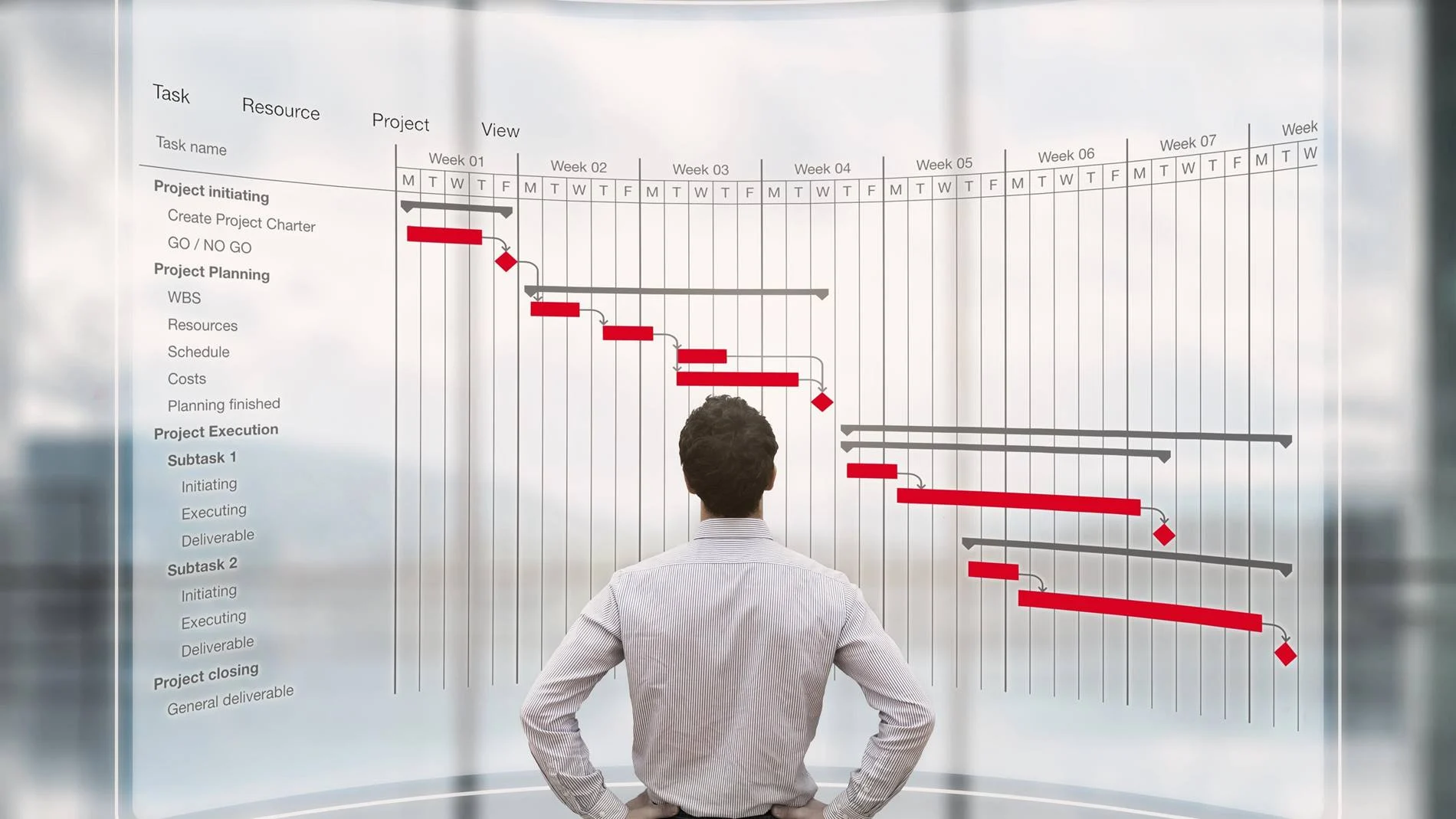

system integration and final assembly. Figure 1 lists the project’s major subassemblies and their tier-1

suppliers.

Furthermore, Boeing came up with a new risk and revenue sharing contract with its suppliers, called the

“build-to-performance” model (as differentiated from the more typical “build-to-spec” or “build-toprint” models). According to the model, contract suppliers bore the non-recurring R&D cost up-front,

owned the intellectual property of their design, and got paid a share of the revenues from future aircraft

sales. Table 1 summarizes the main features of this model. Under this model, the suppliers’ roles were

dramatically changed from mere subcontractors to strategic partners who had a long-term stake in the

project. This model created some risks, which caused extensive integration problems and additional

delays.

Finally, Boeing employed a new assembly method. Subcontractors were required to integrate their own

subsystems and send their preassembled subsystems to a single final assembly site. The goal was to

reduce Boeing’s integration effort by leveraging subcontractors to do more work compared with

previous projects. However, many of these subcontractors were not able to meet their delivery

schedules due to lack of experience in subsystem design and integration, as well as insufficient

guidelines and training. As a consequence, parts and assemblies, which were sent to Boeing for

integration, were missing the appropriate documentation, including instructions for final assembly.

Unanticipated Consequences

Supply chain and design delays increased, as did Boeing’s financial losses, including penalties for late

delivery of the aircraft. CEO McNerney had to face some hard facts based on earlier decisions. He

acknowledged that his new paradigm may have been flawed, “We got a little bit seduced that it would

all come together seamlessly and the same design rules would be applied everywhere in the world and

corners wouldn’t be cut and financial realities wouldn’t hit certain folks.”ii

McNerney’s approach to workers, suppliers, and labor resources was notably off-putting, according to

many in Washington State, Boeing’s corporate home. Since 2011 when Boeing opened its non-unionized

South Carolina assembly plant where salaries were approximately $10/hour less than those of the

unionized workers in Washington Stateiii, worker relationships have been troubled. While admirers have

touted his efficiency and ability to deliver profits, alienated professionals at every level, along with union

members, have described McNerney as “cold-blooded.” One labor specialist stated, “A lot of employees

feel top management doesn’t value them, treats them as expendable…[creating an atmosphere of]

lowered trust, anger and disgruntlement.”iv According to Richard Aboulafia, noted aerospace specialist,

“Management believes if it continues to squeeze suppliers and labor, the problem[s] will be

solved. Again, the track record here is not great. Most of the manufacturing world tell a very

different story. Whether it’s with cars, aircraft or turbines, productivity improvements often

come from the shop floor. That means convincing the people who build things to identify ways

to reduce scrap, improve work flow and eliminate defects. To promote the kind of process

improvements that happen in the factory, a work force needs incentives such as profit-sharing

or other compensation. At the very least, machinists and engineers need to believe their work is

valued. Taking away pensions at a time of record sales is simply a bad way to motivate workers

to go the extra mile. Boeing right now embodies a strange combination of very good and very

bad.” v

McNerney’s management style created its own problems. He vacillated between maintaining his

dispassionate, hands-off general management style with multiple-times per day meetings with

executives during the Dreamliner grounding crisis. His revolving door policy for managers in charge of

the 787 project (four in as many years)vi generated a sense of uncertainty at all levels in the company

and increased pressure to meet goals quickly. This focus on urgency caused him to reflect, after having

resolved the major problems in the Dreamliner, that the plane could have been completed sooner had

Boeing listened more to the customer and less to innovative technology. He said, in a rare interview in

2014, “What I would like to have done is pursued 70 percent of the technology that still would have

satisfied 95 percent of [customer desire]. It would have gotten to them quicker, and it would have cost

us less…You get excited about these projects, and things creep into the design and you lose discipline

sometimes. We just need to be reminded about that.”vii

As described by an anonymous former Boeing executive, “The sense I always got from him in meetings

is that it could have been any business…If we’d been making cameras or autos or doing bond trading, it

would have all been the same to him. The net effect is distancing from the people who come to work

there every day, who bring their hearts and souls to it and want to make it more than a job.”viii

References

Aboulafia, R. (March 9, 2015). Boeing should not lean on labor to cover 787 losses, Aviation Week &

Space Technology. Vol 177, Issue 9: 1.

Anselmo, J.C., C Joseph, and G. Norris. (June 17, 2013). ‘Don’t bet against us,” Aviation Week and Space

Technology. Vol 175 Issue 20: 72.

Anselmo, J.C. and G. Warwick. (July 14, 2014). ‘Not backing off,’ Aviation Week and Space Technology.

Vol 176, Issue 24: 62-64.

Gates, D. (December 1, 2014). Boeing boss Jim McNerney’s turbulent tenure, Seattle Times.

http://www.seattletimes.com/business/boeing-boss-jim-mcnerneyrsquos-turbulent-tenure/ (Retrieved

May 30, 2016).

Hymowitz, C. and T. Black. (January 18, 2013). It’s not his mess, just his to clean up, Bloomberg

BusinessWeek. Issue 4314: 14-16.

Ostrower, J. and J.S. Lublin. (January 24, 2013). The two men behind the 787, The Wall Street Journal.

http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424127887324039504578260164279497602. Retrieved May 30,

2016.

Shenhar, A.J., V. Holzmann, B. Melamed, and Y. Zhao. (2016). The challenge of innovation in highly

complex projects: What can we learn from Boeing’s Dreamliner experience?, Project Management

Journal. Vol 47, No. 2: 62-78.

Wilhellm, S. (April 8, 2015). Boeing’s South Carolina workers make $10 per hour less than those in

Everett, Seattle News. http://www.bizjournals.com/seattle/news/2015/04/08/boeings-south-carolinaworkers-make-10-less-per.html (Retrieved May 30, 2016).

i Anselmo,et al. (6/17/2013). Don’t bet against us.

ii Ostrower, J. and J.S. Lublin. (1/24/2013). The two men behind the 787.

iii Wilhellm, S. (4/8/2015). Boeing’s South Carolina workers make $10 per hour less than those in Everett.

iv Gates, D. (12/1/2014) Boeing boss Jim McNerney’s turbulent tenure.

v Aboulafia R. (3/9/2015). Boeing should not lean on labor to cover 787 losses.

vi Hymowitz, C., T. Black. (1/18/2013). It’s not his mess, just his to clean up.

vii Anselmo, J.C. and G. Warwick. (7/14/2014). ‘Not backing off.’

viii Gates, op cit.

Figure 1: 787 Project’s Tier-1 Suppliers